This study finds that the online “fake news” game, Bad News, can confer psychological resistance against common online misinformation strategies across different cultures. The intervention draws on the theory of psychological inoculation: Analogous to the process of medical immunization, we find that “prebunking,” or preemptively warning and exposing people to weakened doses of misinformation, can help cultivate “mental antibodies” against fake news. We conclude that social impact games rooted in basic insights from social psychology can boost immunity against misinformation across a variety of cultural, linguistic, and political settings.

Research Questions

- Is it possible to build psychological “immunity” against online misinformation

- Does Bad News, an award-winning fake news game, help people spot misinformation techniques across different cultures?

Essay Summary

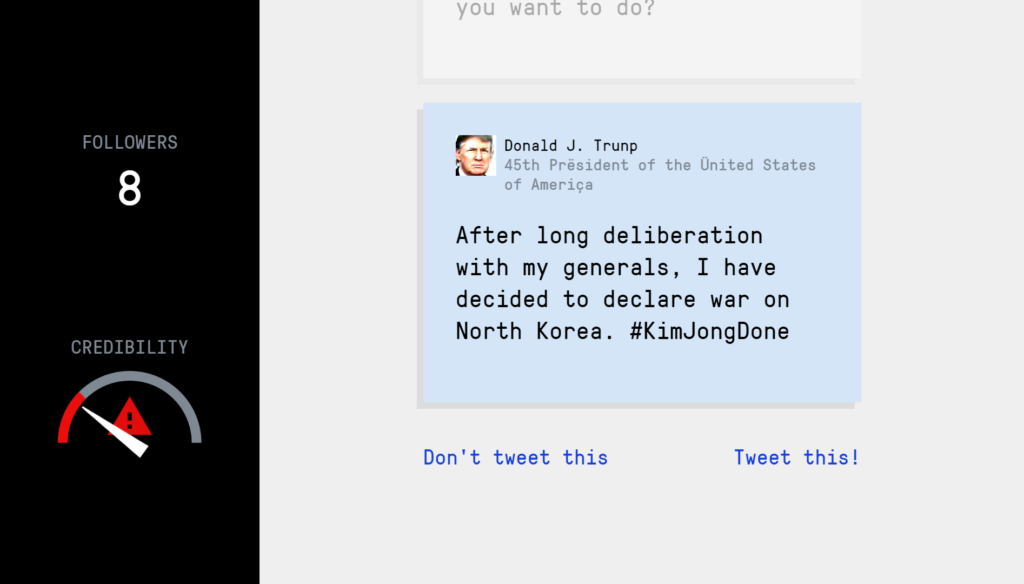

- We designed an online game in which players enter a fictional social media environment. In the game, the players “walk a mile” in the shoes of a fake news creator. After playing the game, we found that people became less susceptible to future exposure to common misinformation techniques, an approach we call prebunking.

- In a cross-cultural comparison conducted in collaboration with the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Dutch media platform DROG, we tested the effectiveness of this game in 4 languages other than English (German, Greek, Polish, and Swedish).

- We conducted 4 voluntary in-game experiments using a convenience sample for each language version of Bad News (n = 5,061). We tested people’s assessment of the reliability of several fake and “real” (i.e., credible) Twitter posts before and after playing the game.

- We find significant and meaningful reductions in the perceived reliability of manipulative content across all languages, indicating that participants’ ability to spot misinformation significantly improved. Relevant demographic variables such as age, gender, education level, and political ideology did not substantially influence the inoculation effect.

Our real-world intervention shows that social impact games rooted in insights from social psychology can boost psychological immunity against online misinformation across a variety of cultural, linguistic, and political settings. - Social media companies, governments, and educational institutions could develop similar large-scale “vaccination programs” against misinformation. Such interventions can be directly implemented in educational programs, adapted for use within social media environments, or applied in other issue domains where online misinformation is a threat.

In contrast to classical “debunking,” we recommend that (social media) companies, governmental, and educational institutions also consider prebunking (inoculation) as an effective means to combat the spread of online misinformation.

Implications

There is a loud call for educational interventions to help citizens navigate credible, biased, and false information. According to the World Economic Forum (2018), online misinformation is a pervasive global threat. UNESCO underscored how all citizens need better up-to-date knowledge, skills, and attitudes to critically assess online information (Carlsson, 2019).

Common approaches to tackling the problem of online misinformation include developing and improving detection algorithms (Monti et al., 2019), introducing or amending legislation (Human Rights Watch, 2018), developing and improving fact-checking mechanisms (Nyhan & Reifler, 2012), and focusing on media literacy education (Livingstone, 2018). However, such interventions present limitations. In particular, it has been shown that debunking and fact-checking can lack effectiveness because of the continued influence of misinformation: once people are exposed to a falsehood, it is difficult to correct (De keersmaecker & Roets, 2017; Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Overall, there is a lack of evidence-based educational materials to support citizens’ attitudes and abilities to resist misinformation (European Union, 2018; Wardle & Derakshan, 2017). Importantly, most research-based educational interventions do not reach beyond the classroom (Lee, 2018).

Inoculation theory is a framework from social psychology that posits that it is possible to pre-emptively confer psychological resistance against (malicious) persuasion attempts (Compton, 2013; McGuire & Papageorgis, 1961). This is a fitting analogy, because “fake news” can spread much like a virus (Kucharski, 2016; Vosoughi et al., 2018). In the context of vaccines, the body is exposed to a weakened dose of a pathogen—strong enough to trigger the immune system—but not so strong as to overwhelm the body. The same can be achieved with information by introducing pre-emptive refutations of weakened arguments, which help build cognitive resistance against future persuasion attempts. Meta-analyses have shown that inoculation theory is effective at reducing vulnerability to persuasion (Banas & Rains, 2010).

The research we present here focuses on an “active” psychological inoculation intervention called Bad News. Bad News is a free choice-based browser game in which players take on the role of fake news creators and learn about 6 common misinformation techniques 1. In our experiments, we showed that the game is effective at building resistance against misinformation (Basol et al., 2020; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019)2. The Bad News game was widely covered in the media and has won several awards (BBC News, 2018a; CNN, 2019; Reuters, 2019) 3. Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2019) co-developed and wrote the game’s content and implemented a survey within the game that players can choose to participate in. This initial evaluation, which involved asking participants about the reliability of several “fake” and “credible” Twitter posts pre- and post-gameplay, showed consistent and significant inoculation effects. This evidence was presented as part of the parliamentary Inquiry on Fake News in the UK (van der Linden et al., 2018) and—in light of further randomized trials and empirical testing—subsequently referred to as “one of the most sustainable paths to combating fake news” by the European Commission (Klossa, 2019, p.23).

In a continuation of the Bad News project, we collaborated with DROG, a Dutch media literacy platform, as well as the United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), to translate and adapt Bad News in a variety of languages in order to promote media literacy worldwide. The purpose of this collaboration was to scale the Bad News intervention in a variety of languages free for anyone to play and access. Thus far, the intervention has reached about a million people. In the research presented here, we evaluate the cross-cultural effectiveness of the game and find support for its efficacy across a range of different cultural and political contexts.

Practically, our game is used as a digital literacy teaching tool (information for educators is available on the game’s website). Importantly, game-based interventions are scalable (i.e., they can reach millions of people worldwide) and offer potential for combating misinformation in other domains as well. For example, we have developed an intervention in collaboration with WhatsApp called “Join this Group”. The game inoculates players against misinformation frequently encountered within the context of direct messaging apps, which are a growing problem in countries such as India, Mexico, and Brazil (Phartiyal et al., 2018; Roozenbeek et al., 2019). Similarly, people can be inoculated against the techniques used in extremist online recruitment by preemptively warning and exposing them to weakened versions of these techniques. In collaboration with the Lebanese Behavioral Insights Unit (Nudge Lebanon), we have developed a game-based intervention called Radicalize, which we recently presented at the United Nations (UNITAR, 2019).

However, it is important to note that digital literacy is complex (Nygren, 2019) and inoculation interventions on their own do not offer a silver bullet to all of the challenges of navigating the post-truth information landscape.

Future research may investigate how inoculation interventions can be combined with other interventions to support critical thinking (Lutzke et al., 2019), evaluations of authentic news feeds (Nygren et al., 2019), and civic online reasoning (McGrew, 2020). Nonetheless, our results show that this real-world intervention can significantly boost people’s ability to recognize online misinformation and improve their resistance against manipulation attempts in a variety of cultural, linguistic, and political settings.